Distance

The journey to this summit is a trek unlike any other. When you look at this fortress wall from the highway, the summit appears to be almost impossible to achieve beyond this impregnable rock fortification. But the key to this ascent is that the access is actually around the back end of the limestone wall. The journey is truly better than the destination.

Follow the trail around the right (northeast) shoreline of Tower Lake to continue up to Rockbound Lake. This is the first heart-thumping part of the climb. There are continual switchbacks straight up through forest, with an elevation gain of very nearly 100 m. It is somewhere up this dirty, dusty section of the trail that you will curse my name. However, it is also the point at which you will wish you had spent the extra time on the treadmill during those long winter nights.

As you come out on the top of this stretch of trail, the unique Rockbound Lake comes into view. Stop and take a breather. Give the old heart a break before attempting to get to the upper plateau. This gorgeous lake is aptly named for the limestone walls surrounding it, with the far shoreline bound by Helena Ridge. Before proceeding up to the plateaus remember to rehydrate, and fill your containers as well. There is still a long way to go and there is no guarantee of water up top. The rock of the eastern main ranges of this area lies flatter than in the more eastern front range mountains. Consequently, they lack the trench-like drainage of the front range peaks, causing the drainage to spread unevenly, and consequently it is not pooled for a long time.

Follow the shoreline to the right, travelling north, until you reach the drainage outflow of the lake. Cross this small stream and continue heading toward the gullies straight ahead. Pick up the trail here that will arrive at the furthest channel on the right. Climb up this gully to embark on the second strenuous part of the trek. This ravine trail is well trodden and maintains its course right up to the upper plateau.

As you emerge from the gully into a small clearing, the summit comes into view behind you. It is almost as far back as can be seen, to the southeast with a bearing of 172º true, 1.9 km distant as the crow flies. As the hiker treks, however, the long ridge walk to the summit is indeed 3 km, with only a slight elevation gain of 356 m. Once you are up and out of this gorge, the remainder of the route becomes a choice between two routes. The recommended time-saving route is to take the low left trail and not the steep climb up to the right. The low trail will descend onto a vast grassy area, which has a lovely clear stream carved through it. At the far end of the grass plateau look for a cairn-marked gully. This is a quick climb back up to the upper terrace. Alternatively, after climbing up from Rockbound Lake, stay to the right, up a steep knoll. The traverse on the upper terrace is longer than the shortcut through the grassy table, but is actually a less complicated approach. Regardless, both routes converge at the upper terrace trail toward the summit. The remainder of the hike consists of a lot of rock hopping on rubble. This first appears to be never ending and becomes rather laborious as you hop on rock after rock after rock. However, as the rock hopping persists, it becomes evident that elevation is being gained without the tedium of a direct route upward. Off in the distance the summit is visible as a rocky outcrop. Clamber to the top of this to reach the exposed summit of Castle Mountain.

The summit is a natural viewpoint with such sights as Pilot Mountain 14.4 km to the southeast and Mount Temple 20 km off to the west. Directly below are the Trans-Canada Highway and the Castle Junction Interchange, a reminder of how far you have come today.

History

This rugged fortress of a mountain was first named because of its obvious appearance, by James Hector of the Palliser Expedition, on August 17, 1858. Dr. Hector had been sent to explore the Bow Valley and search for the source of the Bow River. He was guided by a Stoney guide, Nimrod, who drew a map of the route that Hector should take to find his objective. The map, incidentally, put Hector and his crew on an indirect course, finally coming out of Vermilion Pass, which is today’s Banff-Windermere Highway. He spotted the mountain from a distance of 12 miles, remarking that it “… looks exactly like a gigantic castle,” and named it on the spot.

On January 9, 1946, however, the name was changed to Mount Eisenhower to commemorate a visit by the commander of the allied forces in Europe during the Second World War. That name stuck for 33 years until 1979, when Castle Mountain regained its rightful identity, leaving only the singular southeast pillar of the massif, Eisenhower Tower, named for the US general and president.

In 1883 as rumours of gold, silver and copper in the area spread, Silver City, near Castle Mountain, erupted into a town of over 3,000 inhabitants. John Gerome Healy had a hand in the formation of the town, as he had done some mining at nearby Copper Mountain and had experience building towns, notably forts Whoop-up and Hamilton. These profitable forts were used for the sole purpose of trading whisky to the Natives for buffalo robes.

Healy actually named the town “Copper Mine” but the railway had its own way of doing things and named the stop “Silver City.” The glory was short lived, however, as the five or so mines did not produce any significant profit. There was an unconfirmed report of silver being imported from Montana and planted around Castle Mountain to maintain the excitement and keep the miners in the neighbourhood. Regardless of the efforts, Silver City became a ghost town within two years.

Directions

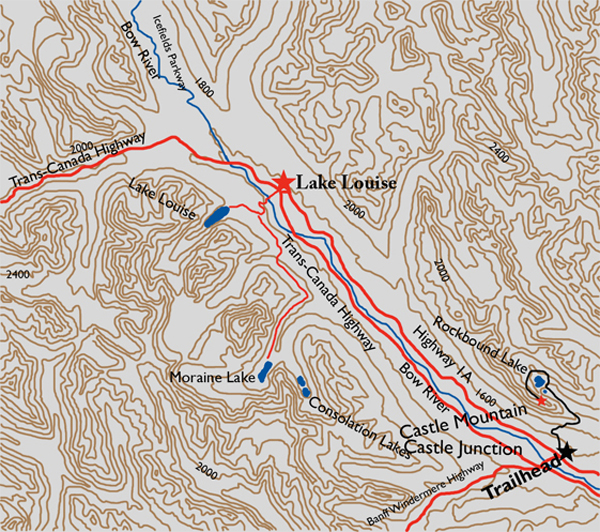

The trailhead is located at Castle Junction, 24 km east of Lake Louise on the Trans-Canada Highway. After exiting at the interchange, head north to Highway 1A and proceed east (right) for 200 m. The trail is marked as the “Rockbound Lake” trail, not the “Castle Lookout” trail.