Distance

Glacier House history

In 1871, the CPR hired a Scot, Sandford Fleming, to find a way around or through many obstacles to the success of a coast-to-coast railway. One of the three biggest challenges was to find a practicable route through the Rockies. The other two were the Laurentian Shield and the canyons of the Thompson and the Fraser rivers. Fleming became chief engineer of the CPR, as he had prior experience as chief engineer with the Intercontinental Railway.

Fleming initially recommended a route through Yellowhead Pass, but this choice was farther north than the CPR desired. The company’s executive committee feared that Us railways would penetrate over the international boundary into Canada if the CPR did not establish a southern route. The final choice cut through the Selkirk Mountains by way of Rogers Pass, even though the Yellowhead Pass was the superior route because it had substantially less elevation change and a longer grade.

Rogers Pass was discovered in 1881 by Major Albert Bowman Rogers. Rogers graduated from Yale University in 1853 and began work as an engineer on the Erie Canal and then with the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad, called the Milwaukee Road. In 1862, during the Civil War, he was a major in the Us cavalry. His reputation with the Milwaukee Road earned him the nickname “The Railway Pathfinder,” which came to the ear of a member of the executive committee of the CPR, James Jerome Hill. Hill hired Rogers in 1881 to command the CPR’s mountain route-finding. Fleming was not directly involved with the appointment of Rogers, but he would oversee the new hire’s work in 1883 and came to praise Rogers highly.

The first order of business for Rogers was to send out exploration parties to survey the Bow River and investigate Howse and Kicking Horse passes. Although early explorers firmly believed there was no workable route through the Selkirks, Rogers’s stubbornness got the best of him and he took on the task himself. He and his party approached the pass from the west, departing from what is now Revelstoke, BC, in June of 1881 by way of the Illecillewaet River. The route was based on an 1866 report by Walter Moberly, a BC government engineer who had had one of his crew view the area from some of the mountains around the Illecillewaet Valley. Moberly insisted there was no pass.

Nonetheless, Rogers was confident that a pass did indeed exist, and from the vantage point of what today is called Mount Sir Donald he saw what he believed to be a workable route. However, the party exhausted their supplies before they could investigate the remaining 29 km of the pass, so they were forced to return the following season. This time, they approached from the east, up the Beaver River, and had to make two attempts, as they again ran out of provisions. Finally, on July 24, 1882, Major Rogers spotted the slope of Mount Sir Donald, the mountain he had climbed the previous summer, and the pass was henceforth known as Rogers Pass. Although he was paid a $5,000 bonus for discovering the pass, the only reward he had agreed to was that the pass be named after him. So he framed the $5,000 cheque and hung it on his wall rather than cash it. This created years of accounting problems for the CPR, and eventually the general manager, William Van Horne, offered Rogers a gold watch if he would just cash the cheque.

With the pass, of course, came the railway bringing tourists to the unexplored, virgin mountains. With most of the principal peaks in Europe already conquered, the summits of North America became a very appealing proposition to professional and amateur mountaineers alike. In 1888, the first recreational ascent of a mountain in North America was achieved by reverends William Spotswood Green and Henry Swanzy when they summited Mount Bonney. This marked Glacier National Park as the base for mountaineering fun in North America barely two years after the park’s formation in 1886.

Once the rail line through to the Pacific was completed, it became obvious that the area of Great Glacier (Illecillewaet) was a uniquely beautiful part of the country. The CPR wasted no time in taking advantage of such magnificence, and by late 1886 had created a lodge of unparalleled elegance: Glacier House. Although Banff National Park obtained national-park status a year before Glacier and Yoho, Glacier House was a first in the Rockies. The Banff Springs Hotel did not open until two years later, and it was Glacier House that became the template for the Chateau Lake Louise.

The logic behind Glacier House was twofold. The CPR needed to have a dining car atop the long, steep climb out of the Rockies to the Selkirks. But dining cars were excruciatingly heavy, and even with specially designed locomotives, they still slowed the climb to the summit of Rogers Pass. To solve this problem, the railway erected a dining hall with a chalet and a few rooms at the base of Great Glacier, which became known as Glacier House. The facility was a great popular success, and it was expanded in 1892 and again in 1904. At its peak, the Great House featured 90 rooms, a billiard hall and a bowling alley. Soon after, a small village, Summit City, sprang up with saloons, hotels, a general store, a school and homes.

Eleven years after the ascent of Mount Bonney by Green and Swanzy, the CPR imported two Swiss guides, Edward Feuz and Christian Hasler, to Glacier House to help develop the region for climbing and assist guests in reaching the summits of these amazing peaks. The idea was to give the lodge’s growing clientele not only a feeling of confidence and safety but also a sense of exotic adventure. By 1903, at least 40 peaks in the Glacier National Park region had been summited, and many of the trails cut by these Swiss guides over a century ago are still used by hikers and climbers today. The guides were a tremendous success and helped to realize Van Horne’s dream of transforming a vast wilderness into a profitable, elegant playground for tourists.

The good times would last for a while, but impending danger has a way of taking the life out of a party sometimes. And so it was with Glacier House, as the unwavering onslaught of snowfall and avalanches caused the eventual demise of both the lodge itself and Summit City. With an average annual snowfall of 12 m at Rogers Pass, and the extreme gradient of the adjacent peaks, it was almost impossible to keep the rail line clear throughout most of the winter and spring. Too many deaths and too many derailments finally forced the CPR mainline under the pass. Van Horne made the decision to tunnel in 1910, and by 1917 the 9-km Connaught Tunnel was complete.

Glacier House continued to receive guests, but without the train pulling up and stopping in front of the grand hotel, most of the appeal was lost. Disembarking at the entrance to the tunnel and travelling the rest of the way by horse and buggy simply did not sit well with tourists. As visitors dwindled, so did Summit City, and in 1925 the hotel was closed for good. In 1929 the CPR did the unthinkable and demolished Glacier House. For fear of fire or collapse, either one causing potential liability, the railway executive decided that the safest end to Glacier House would be to simply take it down.

The next 40 years saw very few travellers. Even with the construction of the Alpine Club of Canada’s A.O. Wheeler Hut in 1946, only a handful of people frequented this stunning landscape. With the completion of the Trans-Canada Highway through Rogers Pass in 1962, the beauty that had been paused, waiting for climbers to return, was finally reawakened once again for us to enjoy. So, drive up to the base of the mountains and the remaining foundations of the great Glacier House and look around in wondrous awe as you pass over the exact same paths that the trailbreakers built in the heyday of this amazing place.

Directions

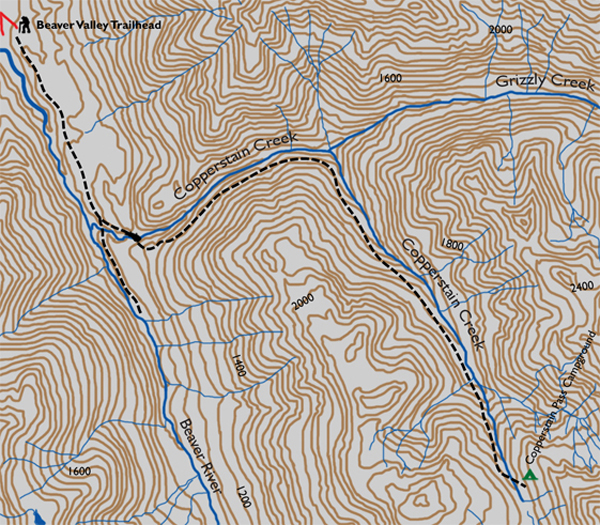

The trailhead originates from the beautiful Copperstain Pass Campground. To get here as the starting point, please refer to the chapter on this campground.

The stretch of 16 km from the Copperstain Pass trailhead near the highway has more than double the elevation gain, for a tally of 1738 m. Therefore, it is recommended as a two- to three-day combined backpacking/scrambling sojourn. With only 525 m of gain, this easy scramble is an extraordinary excursion from the campground.

The peak is unmistakable and ever present, as it is less than 2 km from the campground. From your campsite, after your morning coffee, simply walk through the woods toward the summit. Many faint trails are scattered through the forest, with all of them culminating in a single main path. This route will be picked up quickly. The base of the mountain is about 800 m from the campground, so enjoy the 10- to 15-minute stroll in the forest.

Gradually the woods thin, the ground inclines and you realize you are beginning your ascent. Soon enough the forest breaks and the earth beneath your feet changes to a gentle talus slope. The path that takes you to the summit is well beaten and has negligible scree. Switchbacks are scarce and there is certainly no hand-over-hand scrambling. Lovely. This open, easygoing, enjoyable climb is merely an uphill walk on an open grade.

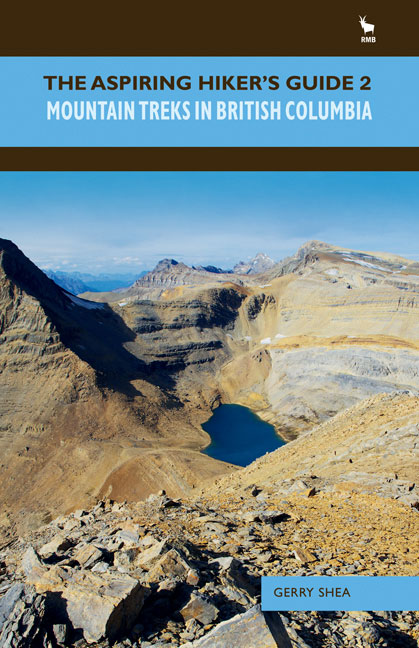

Gerry Shea

“Gerry Shea moved to Kamloops from Vancouver at the age of nine, which is when he became enchanted by the nearby hills. It was on a family vacation many years later that he discovered the mountains and began hiking and climbing in his spare time, gathering knowledge and experience that he has since used to help beginning hikers, scramblers and backpackers to trek safely. Gerry lives in Kamloops with his wife and children.”Excerpt From: Gerry Shea. “The Aspiring Hiker’s Guide 2: Mountain Treks in British Columbia.” iBooks.