Distance

About 500 m into the hike there is a short boardwalk of stairs consisting of about six long platforms. Although the boards are old, there is a distinct smell of damp, exposed wood when they are wet. This smell, combined with that of a few nearby western red cedars and a mossy forest floor, results in a unique scent unlike any other I have experienced in the Rockies.

The exquisite sound of a small stream resonates through the forest as the hike begins a mild uphill climb, and within 20 minutes from the trailhead this stream exposes itself on the right. The path then leaves the stream as it graduates to a much steeper ascent, with sharp switchbacks interspersed with long flat stretches. You’ll cross this same stream again in another 20 minutes or so, and it is the last source of water for the entire climb. Stop here and top up your thirst and canisters.

As the trail winds upward beyond the stream, the forest opens and the view of Field and its rocky guardians becomes ever clearer. This scenery makes the ceaseless climbing tolerable. Another kilometre brings the path to a wide, dry avalanche trench. The power of tumbling snow is evident, as the underbrush and trees have been replaced by a broad swath of rock and rubble. To cross this debris field, follow cairns and a faint track. Once on the other side, follow the cairns up the avalanche slope until the path into the forest reappears on your right. Someone from Parks Canada has packed a chain saw up here to cut a convenient notch in a large fallen tree for us.

For another 45 minutes, the forest gradually thins and the trees become shorter as you reach the subalpine. Look for a tree on the right that has two distinct axe or hatchet wedges hacked from it. An additional 15 to 20 minutes past this tree, on the left side of the open hillside, is a faint path leading to the summit. There are piles of rocks on either side (GPS N51 24 56.0 W116 29 30.4; elevation 1783 m). From this spot, the faint track to the summit of Mount Burgess takes off to the left onto the exposed slope, toward an island of trees that is easily spotted.

Just beyond the Mount Burgess junction, the trail takes up a long section of switchbacks that weaves in and out of the forests. After 15 or 20 minutes of this, the path opens to traverse a disturbingly steep slope of shale. Crossing this slope delivers a fabulous view of the entire length of Emerald Lake, though, from Emerald Lake Lodge at the south (left) end to the lake’s main feeder streams at the north end. The feeder streams come down from glaciers on the President Range, carrying debris and creating a wonderful alluvial fan at the northern end of Emerald Lake. This is just an amazing site. Stop and take it all in; don’t be in a hurry.

Five or ten minutes later, you reach the summit of Burgess Pass, at 7.3 km from the trailhead. From the pass, follow the sign directing foot traffic to Yoho Pass and Yoho Lake. The next half-hour consists of an undulating, forested walk uphill, level and downhill again. There is even a set of wooden stairs. Eventually a large sign prevents you from entering the famous grounds of the Burgess Shale. The massive scree slope of Mount Field dominates the view to the right as the trail breaks from the forest and begins a large left-sweeping curve on its way to Yoho pass and lake.

Find your way onto the slope and begin slogging up the abundance of scree. As you head upward, bear to the far right (east) side of the slope. As mentioned in the introduction to this route, it is necessary to scramble over a rock wall as you near the summit, and by far the easiest – though not the only – route over this wall is through a notch at the far right end of it. But since the area directly beneath the wall is this steep slope of debris that has fallen from it, I strongly recommend that you aim for the notch now, from the base of the scree slope, rather than try to manoeuvre over to it after you come face-to-face with the wall. Traversing the scree diagonally in this way is also a bit easier than trying to go straight up it. There are only a few definitive faint trails on the slope, so just pick your way as you like.

Upon reaching the far end of the wall, look for the openings marked with cairns (I could only find two). Decide for yourself whether the rock climbing, although brief, is your forte or not. The sights from beneath the wall are just as fantastic as the ones from the summit.

Mount Field history

William Van Horne named this easily climbed mountain after Cyrus West Field in 1883. Van Horne was constantly raising money for his railway, and he had brought Field to the Selkirks to court him as a potential investor. Field declined. In hindsight, though, an investment in the CPR would have done well for him and perhaps offset some bad investment decisions he made late in his life which left him penniless.

Born in 1819 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Field was highly educated and had begun working in a textile house at the age of 15. He eventually became the principal in the business, amassing a huge fortune and retiring at the age of 34 in 1853. A few short months later, he was approached by the chief promoter of the Electric Telegraph Company to invest in a trans-Atlantic cable from St. John’s, Nfld., to the Irish coast. After doing his due diligence, Field made the investment and convinced many other New York financiers to get aboard.

After two or three failed attempts, the trans-Atlantic cable was successfully laid, but on September 5, 1858, after only one month of operation, communications failed, as did Mr. Field’s portfolio. He did not waver, however, and by 1865 he had once again raised enough capital to set out to complete this nearly impossible endeavour, only to watch the new line break after 1,300 miles of cable had been laid.

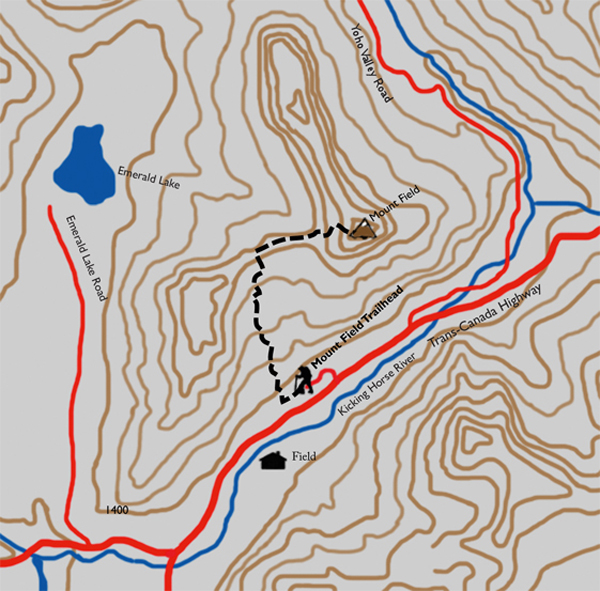

Directions

The first 3.5 km of the trek to the summit of Mount Field takes the same route as Mount Burgess up to the point where the Mount Burgess hike veers off the main trail.

Trailhead: From the Yoho National Park Information Centre in Field, BC, head east on the Trans-Canada Highway for 1.4 km. Turn left (north) onto the only unpaved road and immediately make a left turn at the first fork. Keep left for 400 m and the Burgess Pass trailhead will greet you.

Within the first couple of minutes, you’ll pass a rare find of natural springs on the right side of the trail. There seems to be two or three of these underground aquifers spouting from the hillside and beneath rotting logs. A fork in the path lies just beyond them. Choose the right-hand route.

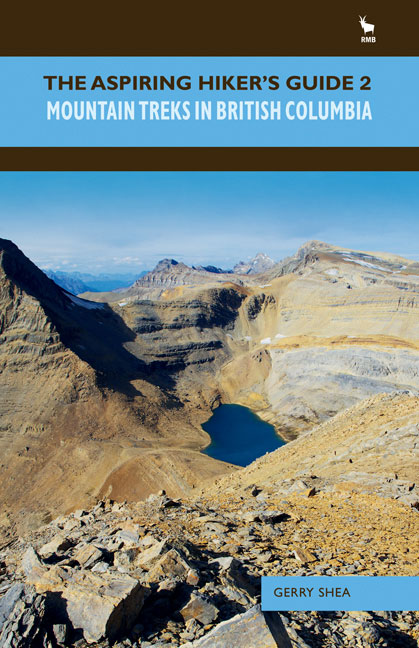

Gerry Shea

“Gerry Shea moved to Kamloops from Vancouver at the age of nine, which is when he became enchanted by the nearby hills. It was on a family vacation many years later that he discovered the mountains and began hiking and climbing in his spare time, gathering knowledge and experience that he has since used to help beginning hikers, scramblers and backpackers to trek safely. Gerry lives in Kamloops with his wife and children.”Excerpt From: Gerry Shea. “The Aspiring Hiker’s Guide 2: Mountain Treks in British Columbia.” iBooks.