Distance

The melt water from the glacier field above gathers to form an unnamed river that tumbles across this exposed plateau. This river, and the next one, the Little Yoho River, must be crossed to achieve the summit of Mount Kerr. But there is a distinct lack of bridges to help you, so you are most likely going to get wet. Many hikers have placed logs and rocks here for easier crossing, but these contributions are still inadequate. Also, there are numerous trails leading uphill on the near side of both these rivers, especially the second one, but do not follow them. Make no mistake: you must cross both rivers, and these two major crossings are about five minutes apart.

We once ran into some fellow hikers here who apparently made this very mistake. They told us they were on their way back down from Kiwetinok Pass. But as we talked with them, we realized they could not have reached the pass. They were directing us to take the trail on the near side of the second river and follow it up to the pass, but when I asked about Kiwetinok Lake, they replied there was no lake. It was obvious they’d made a navigational error and could not possibly have reached the pass by the route they were recommending. They seemed happy with their day’s accomplishment, though, so we saw no reason to set them straight. But the point here is that even though there is a well-trodden path up the near bank of the second river at this spot, you still have to cross the river.

On the far side of the second crossing, search out the abundance of cairns and follow them back downstream to pick up the main trail again. The path resumes in sparse forest and continues to climb gradually, with sporadic steep grades, up to an immense, treeless alpine that will stun you. Up here, the grade levels out substantially and is barely noticeable as you wander toward Kiwetinok Lake. Take time to look around and venture off track. Over to the south (your left), is a nifty little stream that empties the lake and surrounding glaciers and contributes to the birth of the Little Yoho River. Numerous small waterfalls festoon this cool, tranquil stream that has cut its way through the solid limestone beneath the soil you are standing on. It will be necessary to step across this small drainage stream at some point as you approach Kiwetinok Lake, the highest named lake in Canada.

Take a look northward at the slope at the far end of the lake to establish the route you will take up this hillside. Kiwetinok Peak is the striking pinnacle to the left (west) and Mount Pollinger is the summit seen to the right. Between the two, there appears to be a selection of ascents, but the easiest and safest route is the least conspicuous one. The three chutes that are in plain sight are not the way to go. They are too steep and provide limited footing. The clear slope to the far left of the chutes, past the rock bands, should be avoided as well. It looks unencumbered at first, but it leads straight to the dead end of the uppermost wall.

The correct course lies to the right of the right-hand chute. There is a series of horizontal limestone belts that must be overcome. Bypass these around their eastern (right) side. Now backtrack, heading west, without climbing (laterally), to reach a small gap in the uppermost belt. Once through this gap, there is a brief hike to the ridge between the two peaks.

To get there and begin the climb, make your way to the far end of the lake by walking the left shoreline. The descent can be quite dangerous if you decide not to come down this same route. The rock belts are high in spots, and loose rock with narrow ledges should be avoided. I suggest you visually and mentally mark the gap on your way up, so you can find it again on your way back down.

From the ridge the remaining distance to the summit is 320 m to the east, with only 44 m of elevation left to climb. From the summit, Mount Amiskwi is 6.6 km due west, and Mount McArthur is a stone’s throw away to the north.Mount Pollinger history

Edward Whymper and Joseph Pollinger came to the Canadian Rockies together from England in 1901. Officially Pollinger became one of Whymper’s four guides throughout his various climbs in the Rockies, but there were some differing opinions in camp as to what was expected of one another.

Pollinger and the three other guides, Christian Klucker, Christian Kaufmann (Kaufmann Lake) and Joseph Bossonney, were adamant that they were professional mountaineer guides, not cooks or porters. This created some friction during the expeditions, but regardless the party still managed to make first ascents of Mount Whymper, Mount Kerr and Stanley Peak. While in their Vermilion camp on June 29, 1901, Whymper wrote in his journal, as quoted in Roger Patillo’s The Canadian Rockies:

Instructed my people to camp at once as I feared rain and snow but Pollinger and Kaufmann sulked and did nothing and said they wanted food. They did nothing, however, toward preparing it, and when it was ready I observed how hungry they were by going off fishing, without partaking of it.

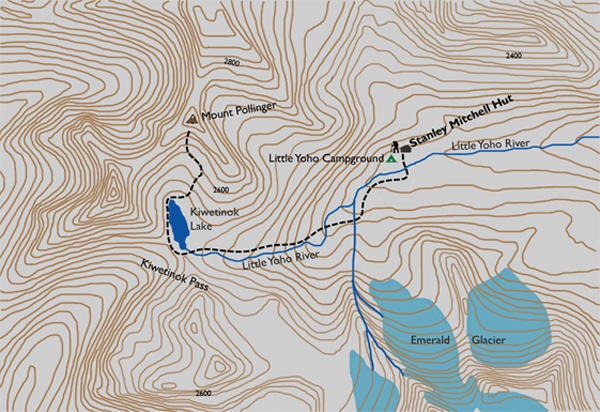

Directions

For directions to the Stanley Mitchell Hut, please refer to the “Little Yoho Campground” hike.

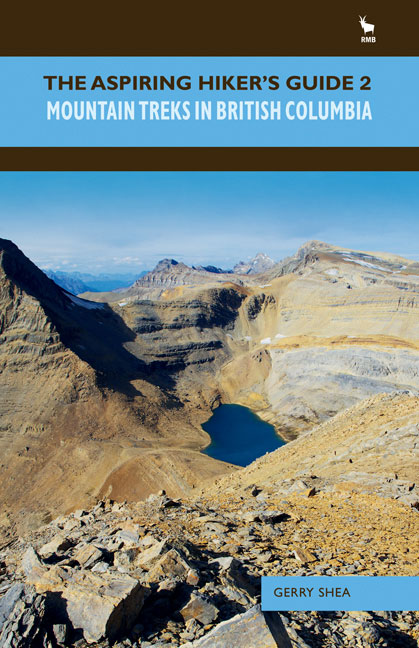

Gerry Shea

“Gerry Shea moved to Kamloops from Vancouver at the age of nine, which is when he became enchanted by the nearby hills. It was on a family vacation many years later that he discovered the mountains and began hiking and climbing in his spare time, gathering knowledge and experience that he has since used to help beginning hikers, scramblers and backpackers to trek safely. Gerry lives in Kamloops with his wife and children.”Excerpt From: Gerry Shea. “The Aspiring Hiker’s Guide 2: Mountain Treks in British Columbia.” iBooks.