Distance

Now the forest opens to a magnificent, long boulder field situated right in the gully you’ve been hiking in as it approaches the base of the mountain. Looking upward to the right, the source of these large boulders becomes obvious. Different obstacles must now be negotiated as deadfall and brush give way to large rocks and massive boulders. The rockhopping begins about 90 minutes into this demanding journey. Initially contained inside the boulder gully, the path stays close to the forest on your left, but as the gully expands, the necessity of crossing this minefield of oversized rocks becomes apparent. Watch for another gulch that enters yours, roughly 20 minutes into the boulder field. From this point, make your way to the right, over huge rocks the size of cars. It’s quite fun, actually, once you establish a rhythm. Not so much fun when the lichen-encrusted rocks are wet and slippery, though, so be careful.

Believe it or not, accomplishing this boulder crossing has only put you in position to scramble up 900 to 1000 m of horrible, horrible, horrible scree. You have been warned, so please do not curse me out halfway up. In all of our discussions with fellow scramblers, when Storm Mountain comes up, it is immediately dismissed as the one that everyone is putting off. The rumours of this scree slope are legendary. And, yes, they are true.

The remainder of the hike is a trudge upward on a giant slope of rocks, pebbles, stones and gravel. “Upward” is obvious, but there is a best route to follow. As you enter the talus slope, you will see a path that has been traced by the drudgery of others. Continue up the belly of the slope, looking for a couple of prominent rock bands several hundred metres up. Stay to the right of these, eventually crossing over the top of them and moving to your left. As you cross leftward over the top of these rock bands, a cliff face is now on your right. Ultimately, you will bypass this by staying left and continue straight up again. As the false summit comes into view you’ll easily see a large cairn slightly to the left. Direct yourself toward this cairn.

At some point you will need to ascertain your position on a mountainside of sliding rock that is simply working you into a state of fatigue. Stop. Take many breaks. Look behind you and enjoy where you are. Gaze out and realize, as you look down at the highway, just how lucky you are. Watch the traffic whiz by, and become aware of your surroundings. You are one of less than one tenth of one tenth of one per cent of travellers that actually get out and do this. Then turn around and get back to work.

The route-finding really is not that difficult; just make sure you follow the trails on the scree to avoid heading into a dead canyon. From the cairn, the summit is still another 250 m up, but as the ascent continues, the grade decreases. Finally you begin to walk on reasonably level ground to approach the true summit over to your right.

Mount Ball’s fantastic snow-covered peak, 6 km to the south, appears to hang over the summit of Storm Mountain, and with its apex at over 3300 m, it is incredibly impressive. To the west are Mount Whymper and Boom Mountain.

Storm Mountain history

Storm Mountain was first successfully climbed by W.S. Drewry and A. St. Cyr and their guide, Tom Wilson, in 1889. The peak was named by George M. Dawson in 1884. Many of Dawson’s explorations to the region had him camped beneath the mountain, and bad weather seems to have been a theme during his visits here.

Dawson, a geologist, anthropologist, author, teacher, civil servant, geographer and paleontologist, was born in Nova Scotia and schooled at McGill College in Montreal, the Royal School of Mines in London and with the Geological Survey of Great Britain. Dawson was teaching chemistry at Morrin College in Quebec when, in 1872, he obtained a position with the Geological Survey of Canada, which brought him out West.

Dawson’s two seasons of exploration, in 1883 and ’84, yielded an incredibly accurate map of the Canadian Rockies from the Red Deer Valley and Kicking Horse Pass down to the Us border. This meticulous map was published in 1886. One noteworthy prize collected during Dawson’s time in the Kicking Horse area was the discovery of a Lower Cambrian trilobite, Olenellus gilberti, along the CPR main line, a quarter of a century before the discovery of the Burgess Shale.

Throughout his career, Dawson’s surveying skills and mapmaking techniques became legendary. In fact, while in present-day Yukon in 1887 his talents foresaw extensive gold deposits. Ten years later, his maps and information were partially responsible for the Yukon gold rush.

George Dawson’s achievements required significant physical endurance and agility. But he also had an exceptional mind and unwavering dedication, and he did more to advance the biological and geological study of western and northern Canada than any other single person in history. This would be an incredible undertaking for any individual, but more so for Dawson, as he lived with Pott’s disease (tuberculosis of the spine), which gave him a deformed spine and a stunted body the size of a 12-year-old boy’s.

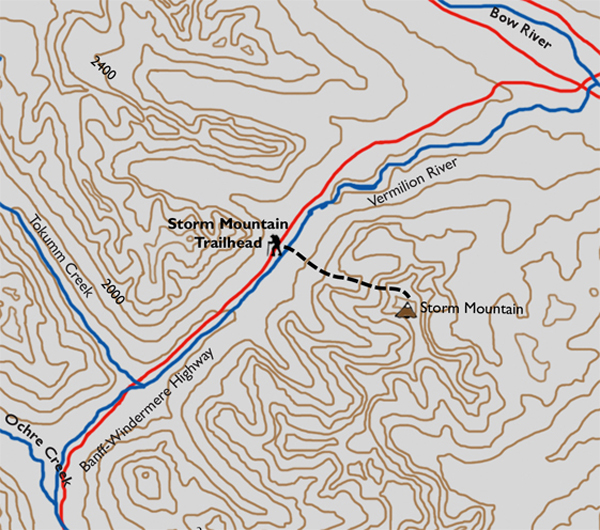

Directions

From the crossroads of the Trans-Canada and the Banff–Windermere highways (Hwys. 1 and 93), travel south for 11.4 km to a small gravel pull-off on the east (left) side of the highway. This is readily recognized, as there is a steel gate inside the pull-off. This parking area is 1.2 km south of the Continental Divide marker, also on the east side of the parkway. The Continental Divide point of interest is 10.2 km south of Castle Junction.

Walk around the steel gate, follow the road and immediately enter a large field. Stroll through the middle of it and make your way to the far left end. Here there is a short, narrow gully taking you down to a stream that is barely too wide to step across. A makeshift bridge of old logs is apparent but slippery. Be careful. Waist-high brush presents the first obstacle for a trail-less beginning.

Past the thick brush, the way opens to the horrific remnants of the 2003 forest fire season and the repetitive deadfall that must be climbed over. This alone becomes exhausting after the first 40 or 50 of these natural obstacles. The stream remains on your right as the trail ventures upward through burnt forest with green undergrowth. Stick close to the stream while searching for a faded track. It is there, so keep an eye out as you continue upward, because about 20 minutes into the trek you’ll find a stack of cairns approximately knee high close to the stream. This marks the beginning of the recognizable trail.

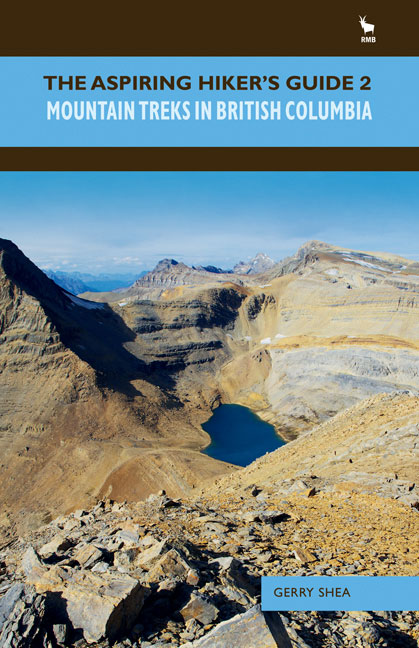

Gerry Shea

“Gerry Shea moved to Kamloops from Vancouver at the age of nine, which is when he became enchanted by the nearby hills. It was on a family vacation many years later that he discovered the mountains and began hiking and climbing in his spare time, gathering knowledge and experience that he has since used to help beginning hikers, scramblers and backpackers to trek safely. Gerry lives in Kamloops with his wife and children.”Excerpt From: Gerry Shea. “The Aspiring Hiker’s Guide 2: Mountain Treks in British Columbia.” iBooks.