Distance

Two kilometres into the hike, you’ll encounter the first of two series of serious switchbacks, lasting about ten minutes. The second sequence occurs after a five-minute break of level walking. Twenty minutes of relentless climbing brings you to a crossing over the same outlet stream you crossed at the start of this journey. Here, the trail has gained 388 m of the 699 m elevation of Honeymoon Pass. The path becomes increasingly overgrown as it travels farther into the backcountry, with the burnt forest thinning out even more. With less shade, and more sunlight seeping through the forest canopy, the forest floor has become overgrown with wildflowers, small shrubs and grasses. After crossing the creek, the hike climbs at an easy, uphill pace without the monotony of switchbacks.

Ninety minutes and 5.6 km from the trailhead, you reach Honeymoon Pass. The vastness of the upper valley appears stunning, as the route suddenly feels as though it is popping out of the narrow pass. Amazing panoramas of the Ball Range are visible to the northeast.

The trail descends 200 m from the pass to the campground 2.9 km away. The path is easy but fraught with multiple creek crossings over bridges commonly made of narrow logs. The valley floor can be quite mushy, too, as marshes reappear throughout after recent rain. Be careful. The campground is primitive, without an outhouse or a bear pole. Take along some rope to hang your food in a nearby tree.

Kootenay history

Unlike Banff, Lake Louise, Glacier and Revelstoke national parks, Kootenay’s beginnings were not influenced by the CPR. This region, with its passes and rivers, was used for trading routes and hunting grounds long before the eventual formation of the park and even longer before the first Europeans arrived.

For centuries the various First Nations had an established economy that integrated trade among them, with some of those relationships spanning great distances. When fur trade by Europeans began to take root in the West, their companies, largely the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, depended almost entirely on Natives to harvest the fur for trade.

The Shuswap and Ktunaxa (Kootenay) Indians were using routes through the Kootenay Park region to trade with the Stoneys across the Rockies as early as the 1700s. And though Europeans later claimed to have discovered these trails, the Natives had already been using them to trade fur with the white man for at least 40 years before white men began using these routes themselves, early in the 19th century.

David Thompson of the North West Company crossed Howse Pass a year after his scouting party, led by Jacques Finlay, bushwhacked the route for him. Thompson had left the relative comfort of Rocky Mountain House on May 10, 1807, and arrived at what they thought was the Blaeberry River on June 30, 1807. As it turned out, they were mistaken and the river was in fact the Columbia, near present-day Invermere. As river travel was quicker and simpler than hiking overland, it was here that Thompson and his party spent a week building boats to continue their exploration. They paused their adventure on July 18, 1807, on the shores of Lake Windermere, where they built log structures they called “Kootenae House” to fend off the upcoming winter and the local Natives.

Although he spent the winter of 1807/08 trading with the Ktunaxa and Shuswap Indians, Thompson did not actually ever venture into the Vermilion or Kootenay watersheds. He came close, and he was in contact with the inhabitants of the territory, but he never set foot into this spectacular eminence of present-day Kootenay National Park.

In 1841 Sir George Simpson became the first non-Native official to set foot in the gorgeous Vermilion drainage system and Kootenay River Valley. Although he was governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company at the time, he was not here on official business. Simpson was on a rapid journey around the world that took him to this region as a through-hiker only; he barely had time to stop and smell the flowers. The river he discovered while on his record-breaking attempt around the globe was named after him in 1858 by Palliser Expedition leader James Hector. Simpson is also the first recorded person to soak in Radium Hot Springs. Apparently, he bathed in a pool that was just large enough to hold one man. Radium Hot Springs would become a major influence in convincing governments to build the Banff–Windermere Highway and to constitute Kootenay National Park.

Later in the same year as Simpson passed through, James Sinclair visited the area as a guide, bringing 23 Red River Métis families to the Columbia River from Winnipeg (then called Fort Garry). They then followed the Columbia to Walla Walla, Washington. Sinclair contracted this favour for the Hudson’s Bay Company even though he was not directly employed by them at the time. Sinclair travelled the same passage as Simpson, entering the Vermilion district to the Kootenay River, coming over White Man Pass and eventually through another pass that would ultimately bear his name. The Hudson’s Bay Company was attempting to gain a presence in the Washington and Oregon territories, and Sinclair’s emigration was a part of this plan. He was put in charge of trade and restoration of Fort Walla Walla in 1853. During an Indian uprising in 1855, Walla Walla was sacked and looted. Fortunately, Sinclair and his party had been ordered to depart just prior to the attack. Nonetheless, he met his demise on March 26, 1856, during an Indian attack on the Cascade Locks settlement, in Oregon.

Four years later a Belgian-born missionary began an arduous adventure that would carry him from Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho, to the Bow River Valley near Canmore, Alberta. The purpose of Father Pierre-Jean de Smet’s trek was to meet and convert the Natives along his route, which he did when he finally assembled with the Chippewa, Cree and Blackfoot in the Canmore region. The direction de Smet took on this endeavour was more or less the reverse of the path taken by James Sinclair in 1841. There is some speculation as to his exact route, however. According to Dr. George M. Dawson, a member of the Geological Survey of Canada, de Smet ventured up the Columbia River to the Kootenay by way of Sinclair Pass, then down the Kootenay to the Cross River. He completed his voyage by following the Cross upstream, finally going over White Man Pass into present-day Canmore. Apparently, the Cross River derives its name from a cross that de Smet erected at some point along the river.

All was quiet through here for another 13 years until the accidental arrival of James Hector of the Palliser Expedition in 1858. Dr. Hector had been sent from Old Bow Fort, near present-day Morley, Alberta, to explore the Bow Valley and search for the source of the Bow River. He was guided by a Stoney Indian, Nimrod, who drew a map of the route that Hector should take to find his objective. The map, incidentally, put Hector and his crew on an indirect course, finally coming out of Vermilion Pass, which is today’s Banff–Windermere Highway (Hwy. 93).

The Palliser Expedition leader named many of the features in the Vermilion and Kootenay basins, including Mount Ball, the Blaeberry River, Castle Mountain, Goodsir Towers, the Purcell Range and Simpson Pass. During his time through here, Hector also found the source of the Vermilion River and the point of its entry into the Kootenay, and followed the Beaverfoot River from the Kootenay to discover the Kicking Horse River (see “Simpson River Trail” for the origin of the name of the Kicking Horse River).

The renowned British mountaineer Edward Whymper arrived in Canada in 1901 at the request of the CPR, which wanted him to help promote the Rocky Mountain adventures and luxuries the CPR was marketing in Britain and Europe. Whymper and his entourage of guides Joseph Pollinger, Christian Klucker, Christian Kaufmann (Kaufmann Lake) and Joseph Bossonney explored the Rockies, Selkirks and Vermilion areas and ascended several of their peaks, including Mount Whymper and Stanley Peak. Soon after this well-publicized exploration, outfitters like Walter Nixon began guiding tourists through these valleys on horseback, blazing many of the trails that are still used today.

In the early 1880s, a settler named John McKay homesteaded in the present-day Radium Hot Springs, staking a claim along the Columbia River, which included the springs. He did nothing to develop the springs, however, and by 1890 a British entrepreneur named Roland Stuart paid $1 per acre for a Crown grant of the 160 acres containing the pool. Stuart’s original plan was to sell bottled water, as it was believed to have medicinal minerals, but when analysis of the water in 1913 revealed the presence of radium, he changed course and began developing a spa that would rival the famous one at Bath, England.

After the initial construction of the bathhouse and pools, Stuart departed for England to join up for the First World War. Before he could return, the federal and British Columbia governments expropriated the land in 1920 for $40,000 as part of the negotiations for the Banff–Windermere Highway. The value of the springs was judged by some to be more in the neighbourhood of $500,000.

Construction of the highway from the Columbia Valley had begun in 1911, but the war put construction on hold. The war left the British Columbia government penniless and unable to complete the highway, so the federal government decided to finish it, with the stipulation that the provincial government turn over a five-mile corridor of land on either side of the highway for a national park.

Directions

From the intersection of the Trans-Canada Highway and the Banff–Windermere Highway (Hwy. 93) at Castle Junction, travel south into beautiful British Columbia. At the 41.3-km mark, the trailhead for Verdant Creek Campground is on the left (east) side of the highway. It is well marked and is just north of Kootenay Park Lodge. There is a designated parking lot, with a marked trailhead.

The route begins in thin coniferous forest but soon becomes enveloped in the scorched reminder of the 2003 wildfire season. Although substantial forest-floor regrowth has begun, the trees themselves still appear lifeless. As with most trails in this region, this one presents a unique experience of openness within closed forest.

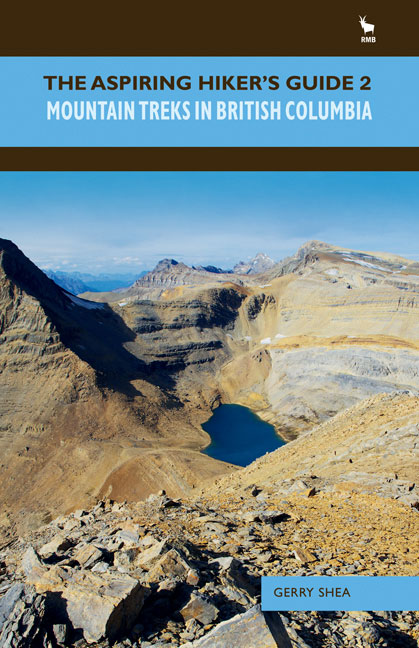

Gerry Shea

“Gerry Shea moved to Kamloops from Vancouver at the age of nine, which is when he became enchanted by the nearby hills. It was on a family vacation many years later that he discovered the mountains and began hiking and climbing in his spare time, gathering knowledge and experience that he has since used to help beginning hikers, scramblers and backpackers to trek safely. Gerry lives in Kamloops with his wife and children.”Excerpt From: Gerry Shea. “The Aspiring Hiker’s Guide 2: Mountain Treks in British Columbia.” iBooks.